If you’ve read my novel, The Edge of Nowhere, you may remember that today marks the anniversary of the granddaddy of all dust storms to hit the Dust Bowl states during the 1930s. It was the storm that coined the term, “The Dust Bowl.”

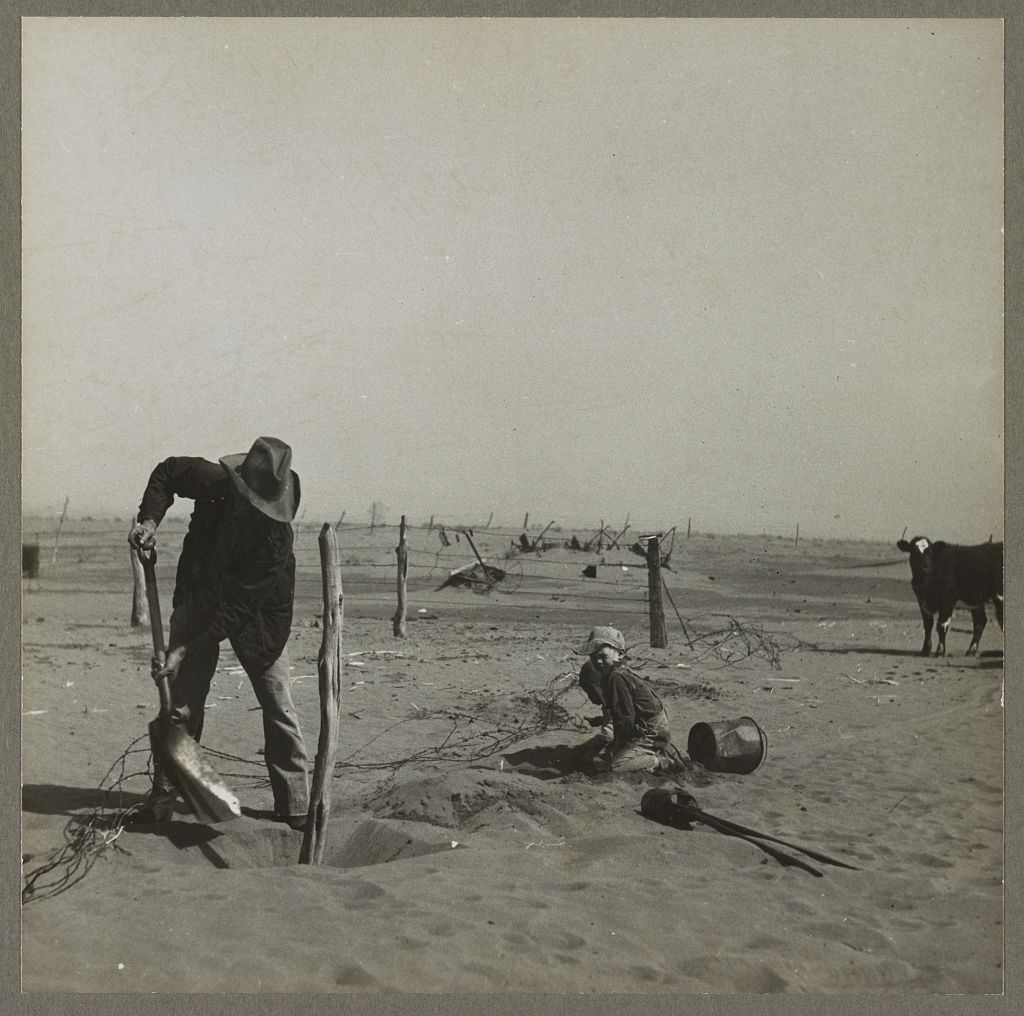

These “black blizzards,” as they were known, began in 1931 and increased in severity and destruction until the first “big one” in May of 1934. It’s hard to imagine what these storms were like, but some of the images below can give you an idea of how shocking they were. Just watching one of these storms come toward you must’ve been terrifying. The dark clouds of dirt completely obliterated the sun, and darkness enveloped the land. When the storms had passed, families carried dirt out of their homes by the bucketload. Forget “sweeping” and “dusting” — families used shovels inside their homes to remove the piles of dirt. And, though they were called Black Blizzards, the dirt didn’t melt like a snow blizzard. Vehicles were found buried almost entirely under several feet of dirt, and the front doors of many homes were blocked such that residents were forced to crawl out windows to reach the outside. And you can only imagine those caught unaware with no means for shelter — theirs was an almost certain fate of death or, at the very least, significant medical complications from inhaling so much of the dirt deep into their lungs.

And then came the big one — April 14, 1935.

It was Palm Sunday, and though the plains states had been immersed for five years in the Hell that became known as The Dust Bowl, it was a day that dawned bright and gave hope for better days ahead. Families went to church, and children enjoyed the warmth of the early spring day. While the dust and dirt in the air was still as pervasive as ever, the sun tried hard to pierce through the dirt hanging in the air. What we didn’t know is that it was a day that would go down in the record books for having the most horrific dust storm in the entire ten years of The Dust Bowl.

When I sat down to write, The Edge of Nowhere, I thought I understood The Dust Bowl. Like all Oklahoma children, I’d taken Oklahoma History. More than that, I’d grown up on the stories of the dust and dirt that entered through every crack and crevice of a home, and I thought I understood the terrible storms that swept through the plains states. The truth is that there is so much I didn’t know. Now, on this 81st anniversary of Black Sunday, I hope to bring some of the information I’ve learned through my research for this novel to you.

By 1935, the dust storms that swept primarily through the states of Oklahoma, Colorado, New Mexico, Kansas and Texas had reached epic proportions. Just the year before in 1934, there were more than 3 dozen reported dust storms — approximately three every month. The first big storm occurred in May 1934 and is said to have travel more than 1500 miles, all the way to Boston, New York, and Washington D.C. FDR is said to have dust from the plains states on his desk at the White House, and the Atlantic Ocean had a thick film of dirt across its surface.

One storm alone took out 1/4 of all of Oklahoma’s wheat crop, 1/2 of Kansas’ crop, and all of Nebraska’s. The economic damage was as devastating as the storms themselves, and this at at time when the whole nation is already reeling from The Great Depression.

But it wasn’t just the storms themselves that made life horrific for those in the heart of destruction — it was everyday life. On a daily basis and in the absence of an active storm, the sky was still overcast with a constant haze of dirt. It got into your eyes and noses, and even into your ears and mouth. If you spit, the phlegm resembled tobacco. On the few occasions when it did rain, it came down like dark droplets of mud. School children had no choice but to go out into the elements and were forced to wear goggles over their eyes to keep the grit out, and wet washrags over their faces to keep the dust from seeping into their lungs. Dust pneumonia was rampant and targeted the young and old primarily. And that was just on a normal day.

But it wasn’t just the storms themselves that made life horrific for those in the heart of destruction — it was everyday life. On a daily basis and in the absence of an active storm, the sky was still overcast with a constant haze of dirt. It got into your eyes and noses, and even into your ears and mouth. If you spit, the phlegm resembled tobacco. On the few occasions when it did rain, it came down like dark droplets of mud. School children had no choice but to go out into the elements and were forced to wear goggles over their eyes to keep the grit out, and wet washrags over their faces to keep the dust from seeping into their lungs. Dust pneumonia was rampant and targeted the young and old primarily. And that was just on a normal day.

The dust storms of the 1930s were dangerous – deadly, even. Unlike a tornado, there was no escape from them. Though you weren’t likely to lose your home or be blown away in a dust storm, the likelihood of dying or succumbing to life-threatening illness by being caught out in a storm was very real. There are stories of farmers slicing open the bellies of cattle after these storms, and the contents revealed stomachs full of dirt and dust. And, though there were only five states in the heart of destruction, there wasn’t a single state in the nation that wasn’t affected. In fact, the term “The Dirty Thirties,” is a direct reflection of the dirt from the Dust Bowl states landing around the nation. The dust quite literally blew everywhere. It was relentless.

Today, on the 81st anniversary of the largest and worst dust storm to ever hit during this era, I’d like to share with you a chapter from The Edge of Nowhere. Though a work of fiction, this novel reimagines some of the trials and tribulations of my own family during the era, as my grandmother raised twelve children alone after the death of her husband in 1934. The excerpt below is taken from Chapter 37, which describes in detail the experiences of my fictional family – Victoria Hastings Harrison Greene, her four small children at that time, and her adopted parents. The depiction of this storm as seen through the eyes of Victoria was taken from a variety of first-hand reports from survivors who lived through this and other storms of the era. Enjoy!

Black Sunday: April 14, 1935

As seen in The Edge of Nowhere

An Excerpt from The Edge of Nowhere by C.H. Armstrong

Used with permission by Penner Publishing

Available in e-book and paperback formats

$2.99 for e-books / $14.99 or less in paperback

Amazon | B&N Paperback | Nook | iBooks | Kobo | Google Play

…The end of February brought snow showers, but it was nothing like I’d ever seen before or since. Instead of beautiful flakes of white powdering the streets, the snow fell in dark flakes of gray and black. It looked like ashes falling from the sky. The dirt and dust now overtook what should’ve been the purity of fresh snow. We wondered how much more we could take of the nothingness that had become our world. Everything was so barren. There just wasn’t ever enough rain to moisten the earth. If ever I wondered what hell looked like, I wondered no more. This was surely hell on earth.

Spring brought warmer temperatures, but still no measurable rain. What rain did come, came down in dark droplets tinged with dirt. Everywhere you looked was just pure ugly. Though spring had arrived, all the beauty had been choked out by the dry, dusty earth.

April of 1935 arrived and, with it, a day I will never forget. Now, almost sixty years later, I still awaken in the dead of night, terrified from a recurring dream that takes me back to that time and place. It was Palm Sunday, and we’d all gone to church that morning. The early part of that day was pleasant. If not for the dirt and dust, the day might’ve been gorgeous. In spite of the barren ground, the sun was shining and brought us hope for better days ahead. We’d returned from church and eaten a light meal, then Father Caleb headed out with several other men to hunt jackrabbits. They’d heard that the fields east of town were overrun, so a party of men gathered to remove them. The jackrabbits often gave us some of our only meals back on the farm, but their numbers were now too large. They were eating every living thing that attempted to grow on the earth. Groups of men had gathered together to try to diminish their numbers and, in the process, they’d each planned to bring back more food for the table—food we didn’t have to pay for.

Jack and Ethan had planned to go with Father Caleb, but the two boys had squabbled endlessly since we’d left church that morning. Frustrated with the both of them, I’d decided to punish them by keeping them home. I’d given them a series of chores as penalty for their behavior. They’d cried and begged to go, but I’d put my foot down and refused to allow it. So Father Caleb went without them.

Around the middle of the afternoon, some hours after Father Caleb had gone, I’d sent the kids out into the backyard. They’d worked hard and I needed them out from under my feet. A short time later, Grace came inside alone.

“Thought you wanted to play outside,” I said to her.

“I did but it’s gettin’ chilly. And the birds are actin’ funny,” she said.

“What d’ya mean?” Mother Elizabeth asked.

“They’re chatterin’ and actin’ all nervous-like. Kinda like they do before a tornado comes through, but the weather ain’t right for it.”

“Where’re the boys?” I asked Gracie.

“In the backyard, playin’ kickball.”

“Out with you,” Mother Elizabeth said, opening the door to escort Grace outside. “It’s too nice to be inside. Go.”

I followed Grace outside and watched the boys kick the ball back and forth to each other. The birds caught my attention immediately. Grace was right; they were acting strangely.

“Mother Elizabeth,” I said. “Come look at these birds. Have you ever seen ‘em act like this before?”

Mother Elizabeth stepped onto the stoop behind me. She watched the birds for a moment, but didn’t say anything. She just shook her head in amusement.

“They seem nervous,” she observed.

“Mama, what is that?” Ethan pointed at the blackened sky some miles away.

Glancing into the distance, I saw what looked like a large cloud moving quickly toward us. Instead of being white and puffy, however, it was pitch black. Mother Elizabeth noticed it at the same time, and the two of us just stared for several seconds, trying to understand what we were seeing.

“Oh, my God!” Mother Elizabeth whispered under her breath. “Victoria—get the children inside. That’s a huge dust cloud!”

Gathering the children, we ran into the house. I dispensed orders as fast as I could come up with them.

“Ethan! Go in the back bedroom and stay with David. He’s probably still sleepin’. Try not to wake him up,” I said. “Grace, find as many washrags as you can and put them in a pot of water. Make sure to put a lid on it!”

“Yes, ma’am.” Gracie and Ethan rushed to do my bidding.

“Jack, help me get some blankets and sheets wet. We’re gonna need to hang ‘em over the doorways and the windows. We wanna cover every crack we can find back in the bedroom with Ethan and David. Those clouds are movin’ in quick.”

“What can I do?” Mother Elizabeth asked from behind me.

“Find some blankets to hang over the top of David’s crib. Let’s try to keep him as covered as possible. Maybe make sure we have a couple more dry blankets we can huddle under if we have to.”

“Caleb—” Mother Elizabeth began.

“I’m sure he’s fine. He’ll have seen those clouds comin’ in and found some shelter.”

Moving quickly, we worked together to prepare the room, but there just wasn’t enough time. Suddenly, the room was darkening around us and time was running out. One moment, the room was filled with light; the next moment was nothing more than shadows.

“Everybody into the bedroom! We need to stay together! Gracie—where is that pot of wet washrags?” I asked.

“Right here, Mama,” she said.

“Go—take them into the bedroom. I’ll be right there.”

Herding everyone in, I’d just closed the door when the entire house went pitch black, like the darkest night. There wasn’t a speck of light anywhere. There was no relief for the darkness. We’d run out of time. The wet blankets dropped uselessly from my hands. I couldn’t see the door to hang them if I’d wanted. The ones we normally kept hanging would have to suffice.

To Continue Reading, use THIS LINK

Leave a comment